Four-Year Study Reveals Unexpected Views of Religious Liberty

What role should religious belief play in public life? The question has taken on new dimensions as the issues have changed and as successive generations are less connected to Christianity, or to religion at all. Although religious liberty questions remain frequently and hotly contested in the political arena, Barna research shows that, at least among Protestant pastors, concern about religious freedom restrictions has actually declined.

One of the foremost challenges to careful thought concerning this question is that public awareness of religious liberty debates is mixed—even among clergy. How do pastors and the general public define terms related to religious freedom, and how do they view its fate in the United States? A recent Barna report, Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture, is the culmination of four years of research conducted in partnership with The Maclellan Foundation examining views of religious liberty among the general population and faith leaders in the United States—Christian and otherwise. We found that although faith leaders and the general public agree on a definition for religious freedom, they have evolving outlooks regarding its future.

Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture

The Religious Freedom Debates - and Why They Matter to All of Us

Consensus Exists on Definition of Religious Freedom: Non-Interference

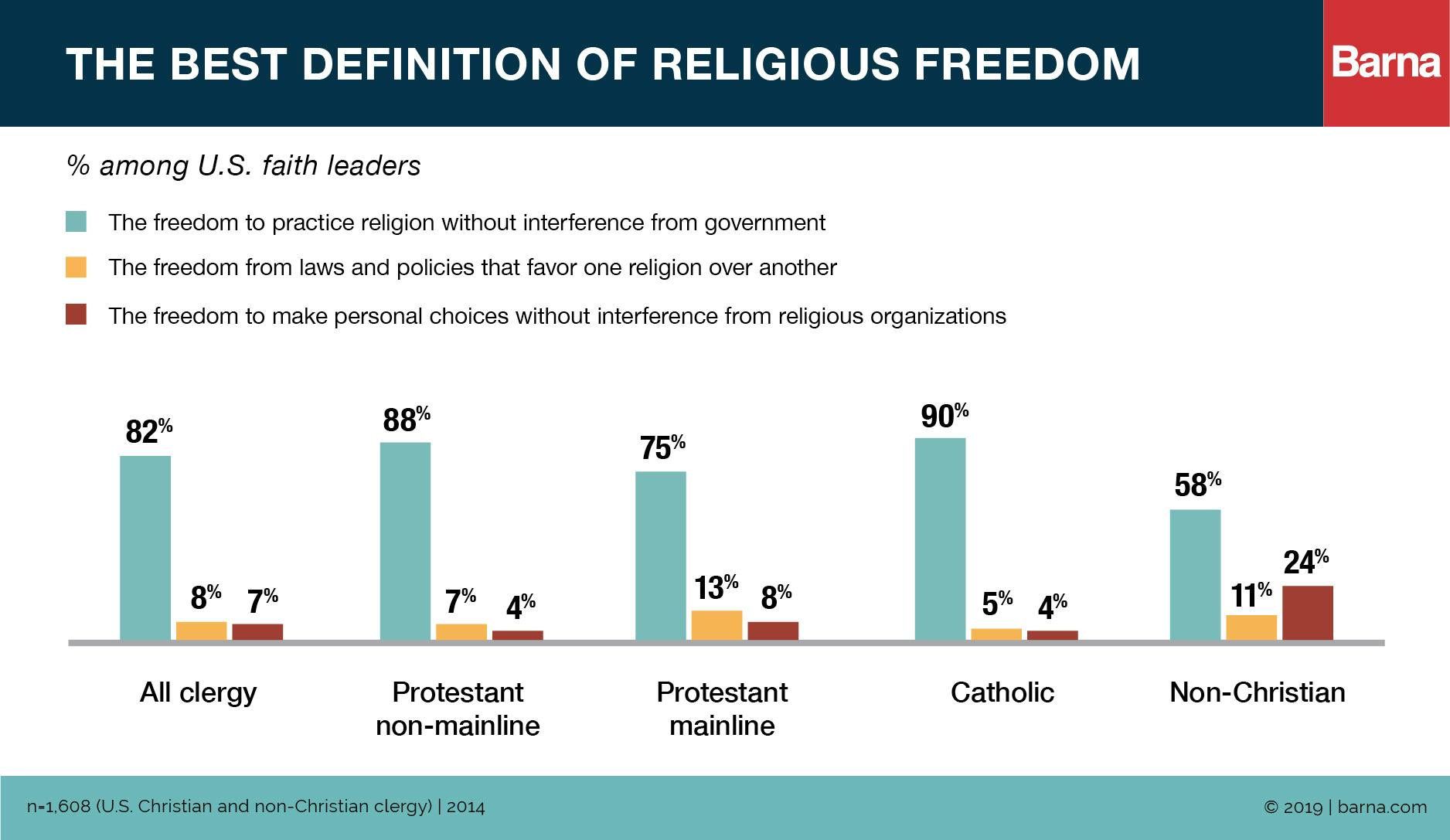

When it comes to defining terms of religious freedom, there is little confusion: Most religious leaders prefer a definition that mirrors the language of the First Amendment—meaning, that the government should not prohibit the free exercise of religion. In a 2014 survey of all Christian and non-Christian clergy, over eight in 10 (82%) said that religious liberty is “freedom to practice religion without interference from government.” Far fewer defined it as “the freedom from laws and policies that favor one religion over another” (8%) or “the freedom to make personal choices without interference from religious organizations” (7%).

These numbers hold true for most segments, but non-Christian clergy (58%) were less likely to choose the majority definition when compared to Catholic (90%) and Protestant non-mainline clergy (88%). Non-Christian clergy are more likely than most other clergy segments (except for Protestant mainline) to say that religious liberty means “freedom from laws and policies that favor one religion over another” (11%) and the most likely (by a significant margin) to say it refers to “the freedom to make personal choices without interference from religious organizations” (24%). As religious minorities in the U.S., non-Christian clergy are likely more willing to embrace government oversight or legal measures to ensure freedom of conscience and equal protection. Among Protestant denominations, African American clergy (69%) are also slightly less convinced that the foundation of religious freedom is governmental non-interference, perhaps also the result of a minority experience.

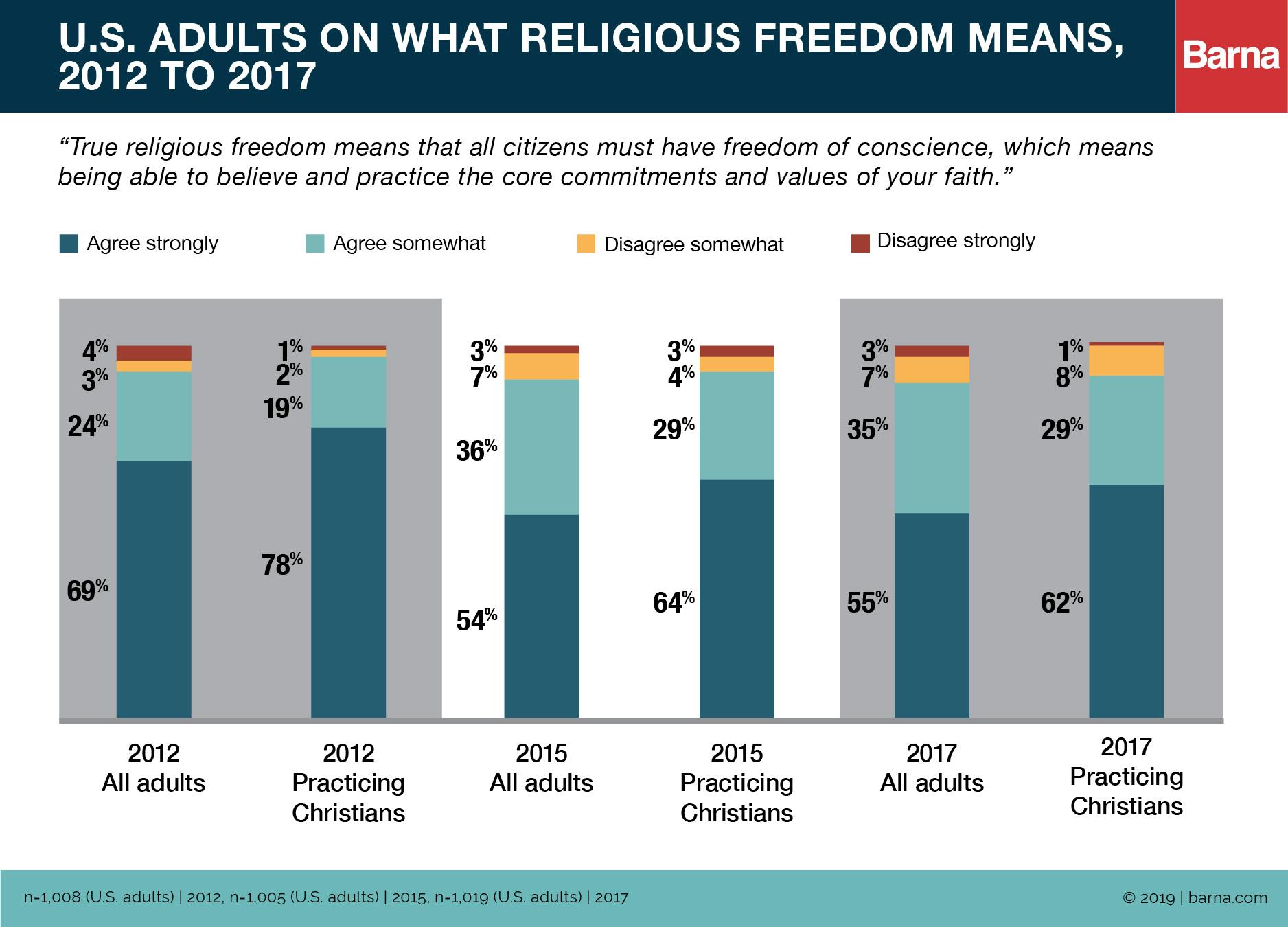

When it comes to the general public, a majority of American adults affirms a similar definition: “True religious freedom means that all citizens must have freedom of conscience, which means being able to believe and practice the core commitments and values of your faith” (55%). However, over the past five years, consensus around this definition has begun to break down. In 2012, 69 percent of Americans favored the definition, but by 2017 that number had fallen to 55 percent. Though most still agree (at least somewhat), it appears American adults are feeling less certain about this definition. The same is true for practicing Christians, who have seen a similar decline from 78 percent in 2012 to 62 percent in 2017.

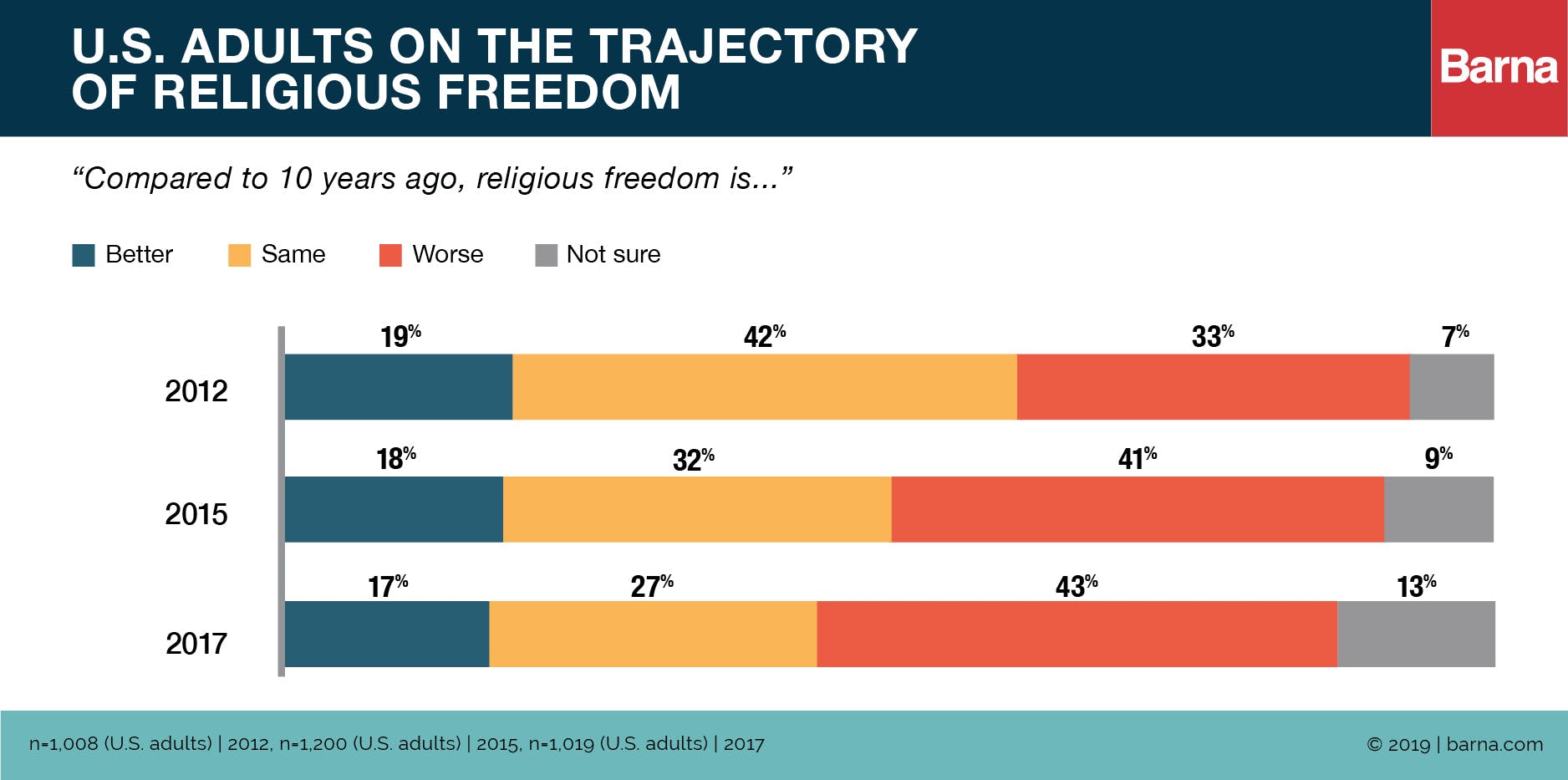

U.S. Adults Believe Religious Freedom in America Is Declining

The general U.S. population believes the state of religious freedom may be compromised. When asked in 2012 if they believe that freedom of religion in the U.S. is worse, better or about the same as it was 10 years before, most said freedom of religion was about the same as it was 10 years ago (42%), while only one-third (33%) said it was worse. This essentially flipped in 2015, when one-third reported it was the same, while four in 10 said worse (41%). That trend continued into 2017, with 43 percent saying it had become worse and fewer saying it was the same (27%). In other words, the general belief that religious freedom in the U.S. is on the decline increased by 10 percentage points over the course of five years.

Protestant Pastors’ Concern About Restrictions to Religious Freedom Is Decreasing

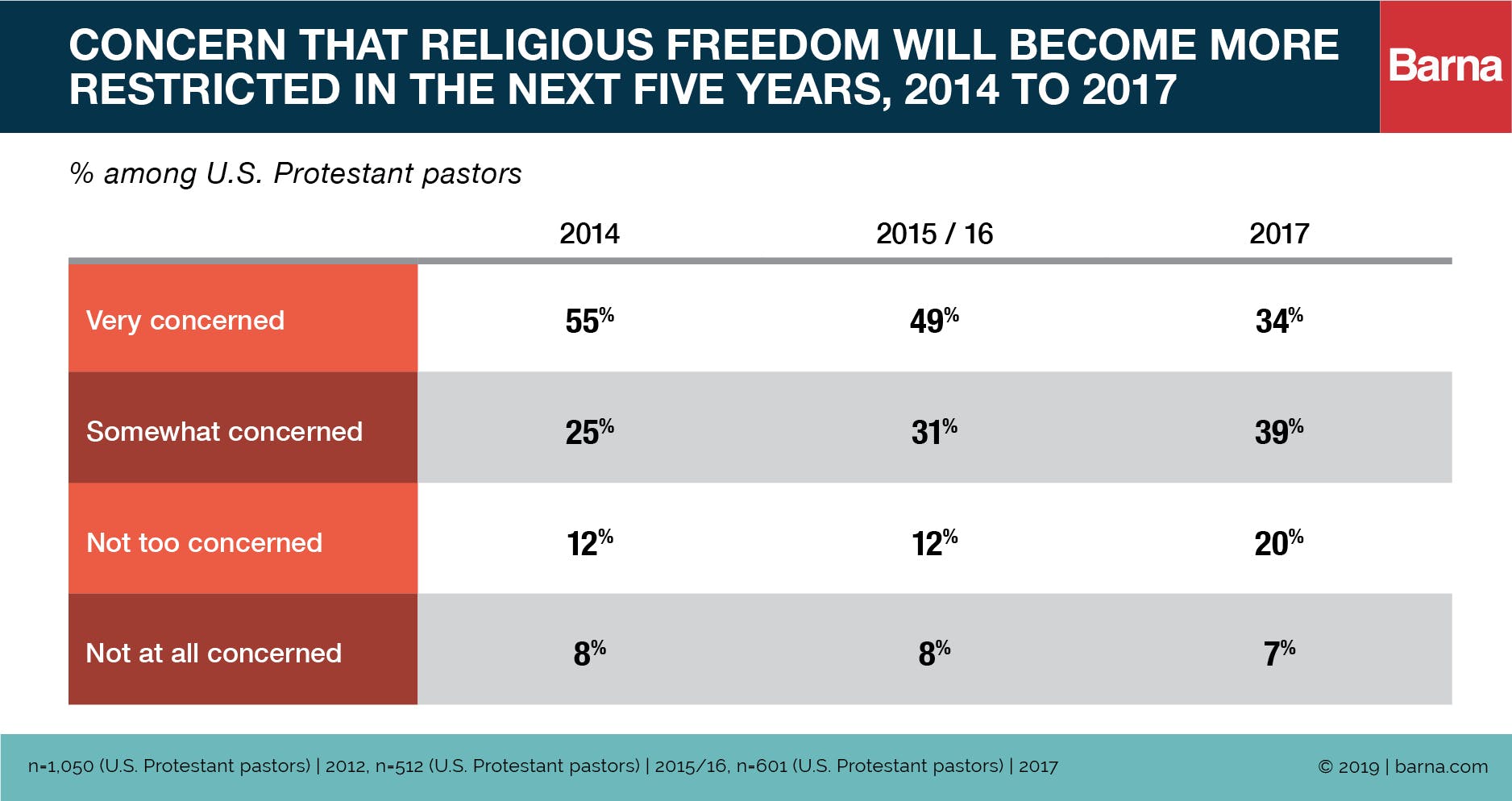

Considering a plurality of the general population believes freedom of religion in the U.S. is worse than it was 10 years ago, one might think that concern would be growing. However, the proportion of Protestant pastors who fear religious liberties may be further restricted in the future has actually dropped. In the 2014 survey of all Christian and non-Christian clergy, over half of Protestant pastors (55%) admitted they were very concerned that religious freedom will become more restricted in the next five years; this percentage fell to below half (49%) in the 2015 / 2016 study and to one-third (34%) in 2017.

If signs of concern waned during these years, it’s not because emphasis on religious freedom was any less prominent in national news. In 2015, in particular, there were several high-profile religious liberty stories, including the controversial passage (and amendment) of the Indiana Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which proponents claimed was intended to restrict government’s ability to infringe on religious rights; the landmark ruling in Obergefell vs. Hodges in the Supreme Court, granting marriage rights to same-sex couples; and threats to repeal the accreditation of Gordon College for their statement of faith on marriage as limited to a man and a woman. Considering these events in light of a perceived drop in Protestant pastors’ concerns about religious freedom, there is perhaps less of a “headline sensitivity” than one might expect.

That said, it’d be incorrect to assume a total lack of concern among Protestant pastors. Most simply shifted away from being “very” concerned to being “somewhat” concerned; the proportion who select this option increased from one-quarter (25%) in 2014 to 31 percent in 2015 / 16, to two in five (39%) in 2017. Protestant pastors who said they were not too concerned about future restrictions of religious freedom increased from one in eight (12%) in 2014 to one in five (20%) in 2017, while the percentage with zero worries held steady (7% “not at all” concerned).

Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture

The Religious Freedom Debates - and Why They Matter to All of Us

What the Research Means

“At Barna, we’ve seen in this and other studies that religion is not a shared value in America the way it once was. But, while the fabric of our social conversation about religion may be breaking apart, this fragmentation provides challenges and opportunities for people of faith in contemporary America,” Roxanne Stone, Barna editor in chief, says. “Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture—the broadest study Barna has yet undertaken on the ways faith in general and Christianity in particular are perceived, expressed and limited in the public square—is focused on how Christian pastors and other faith leaders approach these challenges and opportunities.

“We can be tempted to argue for religious liberty purely on grounds that we need to be left alone—which, the data show, is a common framing for the concept of religious liberty. Or to only elevate our concerns about religious liberty when our religion is under attack, yet cease that concern when we feel protected by those currently in power. However, in doing so, we risk being just another party in the fragmentation of the United States, or another tribal group wanting to protect its right to pull away from other tribal groups,” Stone continues. “On the other hand, if we can make the case for religious liberty as a positive social value for all people, then we are on the right track.

“The research does not provide an explanation for some of the different views between clergy and the general population, such as unexpected levels of concern about the future of religious freedom. But as we look toward that future, effective faith leadership will require humility, discernment and courage,” Stone concludes. “We need humility to see our own blind spots and the experience of others, discernment to know how to think and act and courage to bring faith into the public square—but also courage to accommodate others’ religious freedom.”

About the Research

The statistics and data-based analyses in this study are derived from a series of national public opinion surveys conducted by Barna, among 1,608 clergy in the U.S. in 2014, 513 Protestant pastors in the U.S. in 2015 / 2016 and 601 Protestant pastors in the U.S. in 2017. Responses were collected via telephone and online. Once data was collected, minimal statistical weights were applied to several demographic variables to more closely correspond to known national averages. On questions for which tracking was available, findings from these recent studies were compared to Barna’s database of national studies from the past three decades. Data from the clergy study were minimally weighted on denomination and region to more closely reflect the demographic characteristics of churches in each media market. When researchers describe the accuracy of survey results, they usually provide the estimated amount of “sampling error.” This refers to the degree of possible inaccuracy that could be attributed to interviewing a group of people that is not completely representative of the population from which they were drawn. For the general population surveys, the sampling error ranged from 2.7 to 2.9, for religious leaders, it ranged from 2.2 to 3.9. Major portions of this research was supported by the Maclellan Foundation; Barna Group was solely responsible for the design and analysis of the research findings.

U.S. adults are U.S. residents 18 and older.

U.S. clergy members are leaders in Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and other religious traditions. They are also referred to as “faith leaders” or just “clergy.”

Non-Christian clergy are leaders in religious traditions other than mainstream Christianity.

Christian clergy are pastors of a congregation in a mainstream tradition of Christianity.

Protestant clergy are pastors of a congregation in a Protestant tradition of Christianity.

Mainline clergy pastor in denominations such as American Baptist Churches USA, the Episcopal Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, United Church of Christ, United Methodist Church and Presbyterian Church USA.

Non-mainline clergy pastor in denominations such as charismatic / Pentecostal churches, the Southern Baptist Convention, churches in the Wesleyan-Holiness tradition and non-denominational churches.

Catholic clergy pastor a Catholic parish.

African American Protestant pastors are Protestant clergy who lead congregations that are majority black. Barna recruited a robust oversample of these leaders in order to analyze how their views and experiences may be different from the national average.

Photo by James Coleman on Unsplash

© Barna Group, 2019

About Barna

Since 1984, Barna Group has conducted more than two million interviews over the course of thousands of studies and has become a go-to source for insights about faith, culture, leadership, vocation and generations. Barna is a private, non-partisan, for-profit organization.

Related Posts

America’s Faith Segments Are Divided on Presidential Race

- Faith

-

From the Archives

Americans Struggle to Talk Across Divides

- Faith

-

From the Archives

1 in 4 Practicing Christians Struggles to Forgive Someone

- Faith

-

From the Archives

Lead with Insight

Strengthen your message, train your team and grow your church with cultural insights and practical resources, all in one place.

Get Barna in Your Inbox

Subscribe to Barna’s free newsletters for the latest data and insights to navigate today’s most complex issues.